On a hot February afternoon, a 170-meter container ship pulled into the port of Songkhla. It was hardly full, as southern Thailand’s largest port is not deep enough to support fully loaded vessels.

That adds to costs for exporters, whose cargo must be transferred to larger vessels in Malaysia or Singapore, and less income for the port, which charges handling fees per container and berthing fees by the day. To cut costs, some southern industries avoid Songkhla altogether, sending rubber and lumber by truck across the border to the Malaysian port of Penang.

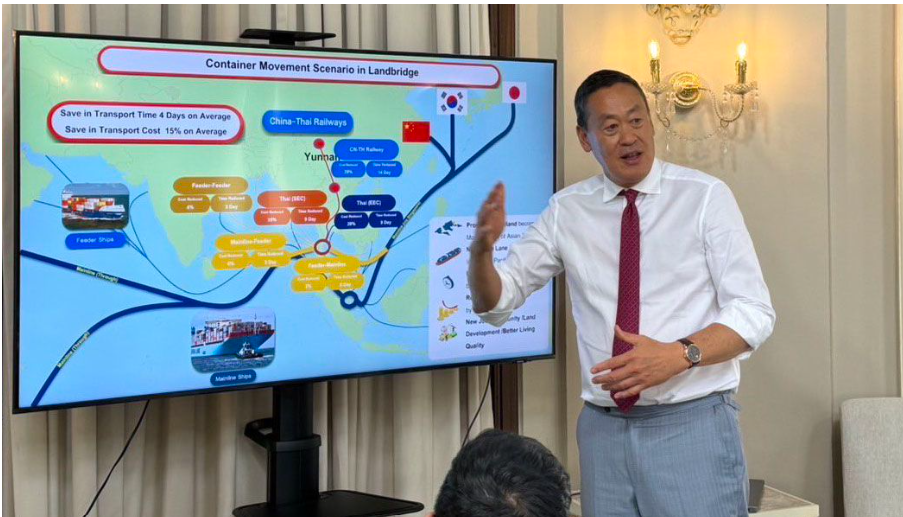

In an effort to grab some of this container traffic and turn Thailand into a logistics hub, Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin has touted a “land bridge” connecting the Gulf of Thailand to the Andaman Sea. By 2030, two new deep-water ports in Ranong on the west coast and Chumphon on the east coast would displace Songkhla as the south’s busiest port, connected by roads and railways stretching 90 kilometers, as well as an oil and gas pipeline.

derstanding of when the product begins its journey and when customers can expect to receive it at their doorsteps.

Thai Landbridge Plan

Roadshows in China and Japan last year and this month in Europe, are seeking to raise 1 trillion baht ($28 billion) from investors for the project, which the Thai government says offers an alternative to the busy Malacca Strait.

But industry experts, opposition politicians and feasibility studies since the 1990s have questioned the land bridge’s financial and technical viability. Shippers and port operators say urgently needed upgrades to Thai seaports would deliver more realistic and immediate returns.

“The first question should be, ‘Where is the demand, and who is the customer?’ Not, ‘What do investors want?'” said Chaichan Charoensuk, chairman of the Thai National Shippers’ Council.

Ships sailing between the Indian and Pacific Oceans, particularly on the high-traffic Far East to Europe route, would reach the land bridge two days earlier than the Malacca Strait, according to the Thai government’s proposal. But a 2022 feasibility study by Chulalongkorn University found that processing cargo at both ends of the land bridge would add at least seven days to the journey.

Compared with the toll-free passage of the Malacca Strait, handling fees across the land bridge would cost 4,640 baht per container, or 23.3 million baht ($653,000) for a large mother vessel.

“It will shorten the sailing distance, but it will use up more time for docking, loading and discharging across the land bridge,” said Sompong Sirisoponsilp, a professor at Chulalongkorn University and author of the feasibility study.